Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

This week, we continue N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with Chapter 6. The novel was first published in March 2020. Spoilers ahead! CW for depictions of racist and misogynist art including some that graphically portrays sexual assault.

“What part of ‘we don’t do bigotry’ do you not understand?”

Chapter 6: The Interdimensional Art Critic Dr. White

Bronca and associates meet with an artists’ collective hoping to show at the Bronx Art Center. The Alt Artistes are male and mostly white; the samples they’ve brought along are also homogeneous—homogeneously bad. Also racist, misogynistic, anti-Semitic, homophobic and “probably some other shit [Bronca] isn’t catching at first glance.” She surveys the offerings, notably a gang-rape triptych and a bronz statue of a man bent over to display a fist-shaped anal gap, then asks the collective’s manager “Are you fucking with us?”

Strawberry Manbun, as she styles him, feigns shock. He’s no better pleased when Bronca formally describes the Center’s mandate to celebrate diversity. The review committee hasn’t seen their “centerpiece” yet. If it rejects this too, Alt Artistes will leave, no hassle.

Collective members carry in a 10×10 canvas shrouded in a tarp, which they remove with dramatic care. Manbun calls it “Dangerous Mental Machines.” At least the painting revealed is real art, combining the techniques of Neo-Expressionism and graffiti to produce the suggestion of a street scene. Bronca recognizes Chinatown, but the figures are faceless ink swirls with grimy hands and blood-stained aprons. Bronca smells wet garbage, hears chattering—no, insect-chittering voices. Weirdly the usual Center noises are muted. The faces in the painting surround her…

A hand jerks her back into reality. It’s Veneza, the receptionist, who’s also weirded out by the painting. The city’s chosen “guide,” Bronca realizes what’s happened. Particle-wave theory, meson decay processes, the “ethics of quantum colonialism,” are all involved, but basically the painting’s an attack meant to destroy Bronca—along with New York.

Manbun and friends have lost their confident smirks. Bronca orders them to cover the painting. She’s remembered what “dangerous mental machines” refers to. So does a furious Yijing. That was Lovecraft’s name for the “Asian filth” who, in spite of undeniable intelligence, lacked souls. What part of “we don’t do bigotry” did the Alt Artistes miss?

The group starts packing their “art.” Bronca doesn’t believe they’re done with the Center, though. And she’s sure none of them produced “Dangerous Mental Machines.” Looking for listening devices, she spots a long white floating—hair?—attached to Manbun’s foot. Even her new knowledge can’t identify it. She asks Manbun who he’s working for. Don’t worry, he replies. Bronca will meet her soon, this time with no bathroom door between them.

Bronca shuts the door in his face. Yijing thinks they should sic lawyers on the group for harassment. Jess, who lost two grandparents to a concentration camp, wants to empty out the Center for the night, even of the workshoppers who actually live in their studios. Veneza finds the Alt Artistes disturbing YouTube channel. Such online garbage attracts cultist-level followers. Center staff need to lock down their internet identities immediately.

After Veneza helps them tighten their digital defenses, Bronca offers to drive her home to Jersey City. The young receptionist has been spooked by the last stall in the bathroom. She knew something was wrong with “Dangerous Mental Machines.” She senses the world has changed since that morning. Bronca needs to explain enough so that Veneza will know the new weirdness is real enough to run from.

Tell her everything, the city whispers. We like having allies, don’t we?

Bronca does her best, then drives to Bridge Park, once a desolate refuge for bums and addicts. It’s been renovated into the bland sort of outdoor space better suited to affluent white newcomers. But the city reassures her that no one will hassle them. This is their place.

Buy the Book

A Half-Built Garden

Beside the Harlem River, Bronca subsumes herself into the city sounds and the underlying metronome that gives them “rhythm and meaning: breathing. Purring.” The city’s only half-awake. Its avatars are scattered. Its streets teem with extramundane parasites. But by the river, the Bronx dreams peacefully. It lets Bronca dance and reveal her power. She makes a massive pipe rise from the water to mimic the angle of her pointing finger. She lifts the whole river into the air. For the first time since her change, she feels neither dread or resignation but joyful acceptance.

The river, she explains, can both float above its bed and flow normally because reality isn’t binary. There are many New Yorks, many worlds. Once there was only one world, full of life. But every decision fissioned off a new world, and those worlds fissioned off new worlds, and so on. Within a world, like New York, every decision and legend and lie add mass until the city collapses under its own weight and comes alive. When that happens, another reality out there, the Enemy’s, tries to kill off the infant city. Bronca can sometimes push the Enemy back. Veneza can’t. When she sees weird stuff happening, and she can’t save Bronca from it as she did earlier, Veneza must promise to run.

In Jersey City, Veneza invites Bronca to stay overnight at her apartment, but Bronca needs to be in New York. As she drives home and feels the city’s welcome, she prays Veneza will be safe.

This Week’s Metrics

Mind the Gap: Bronca takes Veneza to the Bronx River to show off her new “stage of identity formation.” Drive to New Jersey, though, and she’s beyond her place of power.

What’s Cyclopean: The weaponized painting gabbles and gibbers, “like the screechy, chitinous bree of an insect”.

The Degenerate Dutch and Weirdbuilding: Lovecraft’s racism was woven into his art; here Lovecraftian racism woven into art is an even more literal attack on the diversity of New York City. Bronca resists by naming it directly—recognizing the title as Lovecraft’s description of Chinese immigrants, and quoting his nasty assessments of Black and Jewish and Portuguese New Yorkers.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

We’ve encountered dangerous art plenty of times before, from paintings to plays to knitting. Most of those stories, though, are about the power of good art. Sure, The King in Yellow may drive you to madness. Pickman’s photorealistic portraits of ghouls may tell you things you did not want to know about what crawls beneath the surface of Boston. But they can only work such changes on their audience because of their genius. They draw you in, make you believe in what they portray, even if you don’t want to. Weave the right cloth, and you may even attract the attention of gods. Being an artist is a wondrously risky business.

In this chapter, though, we encounter art that’s dangerous because of its flaws. Bad art that mistakes bigotry for transgressiveness. Or art that has deep, enthralling power, undermined by the intrinsic racism at its core. A painting of ghoulish family meals grows more dangerous when you understand the truth behind it. But the artistic attack on Bronca fails when she grasps its truth—because its truth is that it’s lying.

N.K. Jemisin has a long history of puncturing the excuses made for Lovecraft, and naming his prejudices in raw terms. She’s described City as New York Versus Cthulhu, and that’s particularly blunt this week. It also makes clear that this is a universe with both Lovecraft and Cthulhu (or something Cthulhu-like) in it, where Lovecraft was an active tool for his monsters. His dehumanization—his denial of the humanity of those different from him—has the potential to destroy the complex, multicultural, cosmopolitan life of the city he hated. But only if it retains plausible deniability.

We also learn that it’s that multicultural, cosmopolitan life that makes cities come alive. There are so many different ways of understanding a big city—so many different realities coexisting—that they literally connect layers of the multiverse. Layers of neurons, layers of memories, are vital to human sapience. Why not to urban sapience?

This doesn’t, of course, explain why that one obnoxious neighboring reality objects. Perhaps they depend on realities remaining disconnected? The cities themselves don’t know, so neither does Bronca. Perhaps it has something to do with the ethics of quantum colonialism.

Burroughs fighting in the middle of public parks need allies who can act as chauffeurs and sidekicks. Bronca, the city’s memory, needs a foil who can see enough to believe her, who can listen as she practices putting all that ancient knowledge into words. Who can appreciate not only the danger of interdimensional warfare, but the wonder and glory of being a city. Maybe that’s why she doesn’t share Manny’s guilt for bringing someone else into the mess. Or perhaps she realizes, as he doesn’t quite, that ignorance doesn’t actually make for safety when the Enemy is trying to destroy your whole world.

Despite which, she still thinks she’s going to be able to stay out of this fight. Somehow.

It would be nice, wouldn’t it? But the “Alt Artistes” trolling for YouTube views, the doxxing and terrorism, have only gotten worse since Jemisin wrote this chapter. The Enemy has tendrils everywhere, and those who see them are unlikely to escape the responsibility that comes with that vision.

Anne’s Commentary

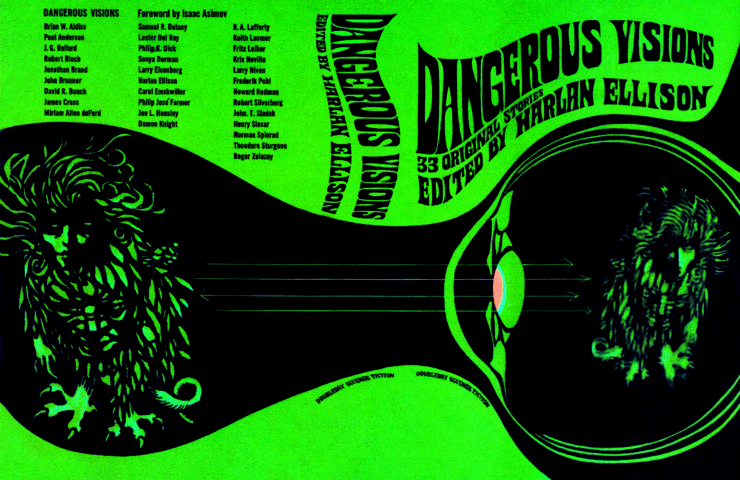

Art can be dangerous. I learned this when my mother bought me a copy of Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions (1967). She didn’t know it was a groundbreaking anthology of all-original stories that would virtually define the New Wave of science fiction and earn awards out the wazoo. She bought it because it was obviously a space and/or monster book, and thus my preferred reading material. Space and/or monster books were generally safe, i.e, sex-free, or so she trusted. Guess she didn’t look inside or read Algis Budrys’ blurb: “You should buy this book immediately, because this is a book that knows perfectly that you are seething inside.” Seething inside was NOT something Catholic schoolgirls did, because seething inside could lead to seething outside, a really dangerous situation.

Behold the first edition book cover!

Here we have an eyeball taking in ray-arrows that resolve within the vitreous fluid into—what? It’s hard to tell without flattening the book to reveal the harpy-like critter on the back cover. See it now, the maiden’s face, the saurian tail, the plumed body, the taloned feet? The act of seeing (voluntary or inadvertent) can please or horrify. Taking in art, literary or figurative or performative, can either feed you—or eat you alive.

That’s if it does anything. Let’s start simplistic and say that art can be good or bad. Good or bad in what senses? The technical, the aesthetic, the pedagogical, the social, the moral—yes, all of those. In Chapter Six, Bronca tells us right off that “The pieces are bad.” She’s referring to the Alt Artistes’ submissions to the Bronx Art Center. How are they bad? She opens with the social and moral aspects. The pieces are “racist, misogynistic, anti-Semitic, homophobic, probably some other shit she isn’t catching at first glance.” This is reason enough for the Center to reject them, given its mission. But they’re also technically and aesthetically bad, “tedious rather than rage inducing.” Boring, in other words, the ultimate criticism.

That the pieces suck apart from their content makes them extra offensive to Bronca, which implies that hateful art can be less offensive if well-done. But Bronca doesn’t really believe haters can make good art. She believes good art “requires empathy.” Is she right?

The painting “Dangerous Mental Machines” lacks empathy, degrading Chinatown and its Asian residents both in its depiction of them and its title, taken from Lovecraft’s correspondence. But its technique is impressive, far beyond anything the Alt Artistes could produce. Bronca admires it for its “intricate patterns within patterns” and its deft incorporation of graffiti sensibility. (It sounds like Bronca’s bathroom mural, which features “a profusion of colors and shapes,” with a “heavily stylized graffitiesque curlicue” for its signature. This isn’t surprising if the Woman in White painted “Machines”; she had plenty of time to study Bronca’s style while lurking in the last stall.)

“Machine” is definitely dangerous art, being a portal into a death trap. Given its racism, Bronca would call it bad art, yet she can’t deny it’s “the real deal,” hence good art. Great art in the way it draws the right viewer into its world, literally. The final critical evaluation might be that “Machine” is bad (socially destructive, immoral) but good (technically, aesthetically) or even great (in its immersive power.)

“Real deal” art is complicated—I don’t think Bronca would argue with that.

Having received a avatar “lexicon,” Bronca knows that the cosmos consists of a “mille-feuille” of worlds, of newer realities layered atop older realities. She visualizes coral columns or “an endlessly growing tree, sprung from a single tiny seed.” Life in one layer or branch would be “unrecognizable to life on another. With one important exception.” Cities “traverse the layers,” at least of all the worlds its residents have dreamed into being. When the layered mass collapses, the city is born, becomes alive.

One of the other realities resents ours, for reasons not given in Bronca’s lexicon. Whenever a city’s born, an agent from that other reality (the city has named it the Enemy) tries to kill the infant power. Always before, the Enemy has manifested as an enormous monster that flopped around destroying infrastructure like the Williamsburg Bridge, a behemoth innocent in its way, like Godzilla or King Kong. But this morning, with the behemoth’s defeat, the Enemy has changed tactics. The city calls the Enemy “different now, craftier, crueler.” It’s decided that to defeat humanity, it must imitate humanity, a crafty species for sure, and too often cruel. The Woman in White has become the Enemy’s avatar; desiring minions, she can either recruit the craftier and crueler humans or forcibly convert the general public into parasite-controlled drones.

Against this changed Enemy, the city and its subavatars must employ not minions but allies. “Allies” is what the city in Bronca’s head calls them; it, they, like having allies—“real ones, anyway.” A “real” ally could be someone like Veneza, a volunteer. The “unreal” allies? They could be the people who, as Bronca says, “just serve the city’s will, as needed.” Manny was disturbed by the idea of such assistants. Bronca, the lexicon-keeper, knows such assistants exist. Will-servers.

How are they different from minions, since they’re conscripted into action? I guess you could look at it this way. The Woman in White’s minions don’t belong to her reality; they’re being forced to serve a foreign power. Whereas the City’s allies could be fulfilling a civic obligation? Functioning as a cell in the City’s body—serving the welfare of the whole—does the cell need a vote?

So far Bronca is exercising her autonomy; despite repeated urges to seek out her fellow subavatars, she clings to the duties and concerns of her personal life.

How much longer can she hold out? I measure it in story-time hours. If that.

Next week, Tara Campbell’s “Spencer” explains the psychology of dolls. You can find that story along with other such explanations in Cabinet of Wrath: A Doll Collection.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.